Barack Obama's Law : Personality: Harvard Law Review's first black president plans a life of public service. His multicultural background gives him unique perspective.

Barack Obama stares silently at a wall of fading black-and-white photographs in the muggy second-floor offices of the Harvard Law Review. He lingers over one row of solemn faces, his predecessors of 40 years ago.

All are men. All are dressed in dark-colored suits and ties. All are white.

It is a sobering moment for Obama, 28, who in February became the first black to be elected president in the 102-year history of the prestigious student-run law journal.

Yet Obama, who has gone deep into debt to meet the $25,000-a-year cost of a Harvard Law School education, has left many in disbelief by asserting that he wants neither.

"One of the luxuries of going to Harvard Law School is it means you can take risks in your life," Obama said recently. "You can try to do things to improve society and still land on your feet. That's what a Harvard education should buy--enough confidence and security to pursue your dreams and give something back."

After graduation next year, Obama says he probably will spend two years at a corporate law firm, then look for community work. Down the road, he plans to run for public office.

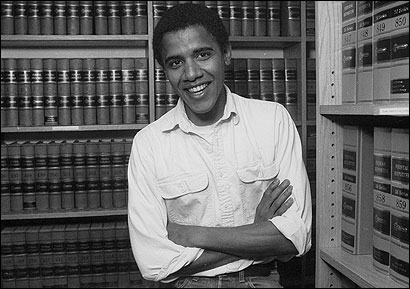

The son of a Kenyan economist and an American anthropologist, Obama is a tall man with a quick, boyish smile whose fellow students rib him about his trademark tattered blue jeans.

"I come from a lot of worlds and I have had the unique opportunity to move through different circles," Obama said. "I have worked and lived in poor black communities and I can translate some of their concerns into words that the larger society can embrace."

His own upbringing is a blending of diverse cultures. Born in Hawaii, where his parents met in college, Obama was named Barack (blessed in Arabic) after his father. The elder Obama was among a generation of young Africans who came to the United States to study engineering, finance and medicine, skills that could be taken back home to build a new, strong Africa. In Hawaii, he married Obama's mother, a white American from Wichita, Kan.

Two years later, Obama's parents separated and he moved to a small village outside Jakarta, Indonesia, with his mother, an anthropologist. There, he spent his boyhood playing with the sons and daughters of rice farmers and rickshaw drivers, attending an Indonesian-speaking school, where he had little contact with Americans.

Every morning at 5, his mother would wake him to take correspondence classes for fear he would forget his English.

It was in Indonesia, Obama said, where he first became aware of abject poverty and despair.

"It left a very strong mark on me living there because you got a real sense of just how poor folks can get," he said. "You'd have some army general with 24 cars and if he drove one once then eight servants would come around and wash it right away. But on the next block, you'd have children with distended bellies who just couldn't eat."

After six years in Indonesia, Obama was sent back to the United States to live with his maternal grandparents in Hawaii in preparation for college. It was then that he began to correspond with his father, a senior economist for the Kenyan finance ministry who recounted intriguing tales of an African heritage that Obama knew little about.

Obama treasured his father's tales of walking miles to school, using a machete to hack a path through the elephant grass--the legends and traditions of the Luo tribe, a proud people who inhabited the shores of Lake Victoria.

He still carries a passbook that belonged to his grandfather, an herbalist who was the first family member to leave the small Kenyan village of Alego, move to the city and don Western clothes.

"He was a cook and he used to have to carry this passbook to work for the English," Obama recalls. "At the age of 46 it had this description of him that said, 'He's a colored boy, he's responsible and he's a good cook.' "

Two generations later, at the most widely respected legal journal in the country, the grandson of the cook is giving the orders.

Yet some of Obama's peers question the motives of this second-year law student. They find it puzzling that despite Obama's openly progressive views on social issues, he has also won support from staunch conservatives. Ironically, he has come under the most criticism from fellow black students for being too conciliatory toward conservatives and not choosing more blacks to other top positions on the law review.

"He's willing to talk to them (the conservatives) and he has a grasp of where they are coming from, which is something a lot of blacks don't have and don't care to have," said Christine Lee, a second-year law student who is black. "His election was significant at the time, but now it's meaningless because he's becoming just like all the others (in the Establishment)."

Although some question what personal goals motivate Obama, his interest in social issues is deeply grounded.

At Occidental College in Los Angeles, Obama studied international relations and spent much of his time helping to organize anti-apartheid protests. In his junior year, he transferred to Columbia University, "more for what (New York City) had to offer than for the education," he said.

After graduating, Obama landed a job writing manuals for a New York-based international trade publication. Once his college loans were paid off, he took a $13,000-a-year job as director for the Developing Communities Project, a church-based social action group in Chicago.

There, he and a coalition of ministers set out to improve living conditions in poor neighborhoods plagued by crime and high unemployment. Obama helped form a tenants' rights group in the housing projects and established a job training program.

"I took a chance and it paid off," he said. "It was probably the best education that I've ever had."

After four years, Obama decided it was time to move on. He wanted to learn how to use the political system to effect social change. He set his sights on Harvard Law School, where he quickly distinguished himself as a top student. He was soon chosen through the strength of his writing and grades to serve as one of 80 student editors on the law review.

Unlike many peer-review professional journals, the law review is run solely by students. It is widely considered the major forum for current legal debate and consequently is watched closely by courts around the country.

In his second year at law school, Obama decided to run for law review president after a conversation with a black friend.

"I said I was not planning to run and he said, 'Yes you are because that is a door that needs to be kicked down and you can take it down.' "

It was a marathon selection process, an arcane throwback to the early days of the review. The students editors deliberated behind closed doors from 8:30 a.m. until early the next day. The 19 anxious candidates took turns cooking breakfast, lunch and dinner for the selection committee, whose members emerged with a historic decision.

"Before I could say a word, another black student who was running just came up and grabbed me and hugged me real hard," Obama recalled. "It was then that I knew it was more than just about me. It was about us. And I am walking through a lot of doors that had already been opened by others."

But few students at the law review were prepared for the deluge of interview requests for Obama from newspapers, radio and television stations. Strange letters of congratulations began arriving.

Shortly after the elections, a package turned up at the law review office with no return address. Obama said he hesitated to open it because of the spree of recent mail bombings targeted at civil rights activists nationwide. When the package was finally opened, inside were two packages of dim sum, with no explanation.

Some students made light of the media invasion, posting a memo titled "The Barack Obama Story, a Made for TV Movie, Starring Blair Underwood as Barack Obama."

Yet tensions were building. White students grumbled about the attention paid to Obama's race. Black students criticized him for not choosing more blacks for other top positions at the review. Caught in the cross-fire, Obama, who has a tendency toward understatement, downplayed his own achievements.

"For every one of me, there are thousands of young black kids with the same energies, enthusiasm and talent that I have who have not gotten the opportunity because of crime, drugs and poverty," he said. "I think my election does symbolize progress but I don't want people to forget that there is still a lot of work to be done."

Describing Obama, fellow students and professors point to a self-confidence tempered by modesty as one of his greatest attributes.

"He's very unusual, in the sense that other students who might have something approximating his degree of insight are very intimidating to other students or inconsiderate and thoughtless," said Laurence Tribe, a constitutional law professor. "He's able to build upon what other students say and see what's valuable in their comments without belittling them."

But what truly distinguishes Obama from other bright students at Harvard Law, Tribe said, is his ability to make sense of complex legal arguments and translate them into current social concerns. For example, Tribe said, Obama wrote an insightful research article showing how contrasting views in the abortion debate are a direct result of cultural and sociological differences.

As law review president, Obama is the last person to edit student articles, as well as longer pieces by accomplished legal scholars. The review publishes eight times a year and receives about 600 free-lance articles each year.

Referring to his fellow students at the review, whom he edits, he said: "These are the people who will be running the country in some form or other when they graduate. If I'm talking to a white conservative who wants to dismantle the welfare state, he has the respect to listen to me and I to him. That's the biggest value of the Harvard Law Review. Ideas get fleshed out and there is no party line to follow."

Obama spends 50 to 60 hours each week on law review business. The full-time volunteer job leaves little time for an additional 12 hours of class, plus homework. When it comes to choosing between the two, as it often does, Obama usually misses class.

One of Obama's most difficult tasks as editor in chief is keeping the peace amid the clashing egos of writers and editors.

"He is very, very diplomatic," said Radhika Rao, 24, a third-year law student from Lexington, Ind. "He is very outgoing and has a lot of experience in handling people, which stands him in good stead."

Tina Ulrich, 24, a third-year student, wrote an article for the review that went through several editors before her final draft landed on Obama's desk.

"When he sent it back, it had lots of tiny print all over it and I was just furious," she said. "My heart just sank. But it was accompanied by specific examples of how parts could be made better. He wound up getting an enthusiastic response from a very tired writer."

Outside the review, other blacks at Harvard are skeptical that Obama's appointment will change much at the Ivy League institution, where 180 out of 1,601 law students are black.

"While I applaud Obama's achievement, I guess I am not as hopeful for what this will mean for other blacks at Harvard," said Derrick Bell, the school's first black tenured law professor.

"There is a strange character to this black achievement. When you have someone that reaches this high level, you find that he is just deemed exceptional and it does not change society's view of all of the rest."

Source

No comments:

Post a Comment